Analysis of the Evolving Power Structure of Federal Units in Central Burma

Photo: People of Sagaing Show Their Support for Operation 1027 and Ethnic Revolutionary Organisations (Photo: Sagaing Region Strike Forces’ Facebook Page)

Briefing Paper on Federal Unit Politics of Central Burma (part 2), By; Centre for Ah Nyar Studies

3 December 2025

The emergence of federal units in central Burma marks a major shift in the country’s revolutionary politics, shaped by the political dynamics of the Spring Revolution. Although this development has been influenced to some extent by the federal principles articulated by actors involved in the NCA process before the coup, as well as by the longstanding principles of ethnic revolutionary groups, the formation of federal units has been driven primarily by the latest discussions after the coup. In the meantime, central Burma has become a testing ground for revolutionary governance, shaped by various armed and political actors working towards a common goal.

While Part (1) of this series traced the origins and formation of these federal units, Part II examines the power structures within the three units. The analysis aims to uncover how central authority is organised, distributed, and contested, and to offer insights into the political struggles at the regional (federal unit) level amid growing calls for NUG reform.

Constituent Base of Power

The power structure of the federal units is shaped by three overlapping sources of legitimacy: electoral, revolutionary, and civil. These cores altogether create a hybrid political order that is neither traditionally parliamentary nor purely revolutionary. This hybrid nature is still a new concept in the political history of Burma.

Sources of Legitimacy

Electoral legitimacy derives from the 2020 elected MPs who constitute the unit parliaments. The 2020 General Elections were an electoral process established under the military-drafted 2008 Constitution. Under that Constitution, the terms of the parliaments were set at five years (see Sections 119, 151 and 168[1]). However, the Constitution was completely abolished by the Committee Representing the Pyidaungsu Hluttaw on 31 March 2021[2]. Since then, the new terms of the unit parliaments have been defined as lasting until the emergence of new parliaments under a permanent constitution developed for each region (see Section 58 of the Magway Interim Arrangements; Section 65 of the Mandalay Interim Arrangements; and Section 51 of the Sagaing Constitution).

Unit parliaments have very limited capacity to exercise territorial authority due to displacement, weak administrative structures, and the complex dynamics of post-coup actors. Nevertheless, their presence provides continuity with pre-coup democratic mandates and offers both local and international legitimacy. The unit parliaments also confer legality on the interim arrangements and serve as the principal bodies for legislative oversight during wartime.

Revolutionary legitimacy arises from resistance groups that have gained authority through territorial control or influence within the units. These groups include the “3-Ps” (People’s Defence Team, People’s Administration Team, and People’s Security Team) of NUG and the Local People’s Defence Forces (LPDF). Their legitimacy is grounded in the practical authority they exercise through on-the-ground governance and the provision of security. A closer look at the leadership and the composition of resistance groups, four broad community clusters can be identified: youth groups, political parties (primarily the NLD), students’ unions, and local labour and peasant communities. Youth groups involved in national and regional youth policy processes between 2015 and 2020 now form the core of youth-led resistance groups in the region, while the NLD youth wings in the three regions (now federal units) and other democratic political parties have also joined the armed resistance. In central Burma, the Myay-Latt and upper Burma divisions of the All Burma Federation of Students’ Unions, along with several university students’ unions, joined various armed organisations after the coup. In addition, local labour and peasant communities also stepped forward to take up arms and fight against the military junta following the coup.

Despite differing levels of participation in the political process surrounding the interim arrangements, no direct involvement of resistance groups was found in Sagaing, whereas such involvement was evident in Magway and Mandalay (as reflected in categories 6 and 4 of their respective drafting bodies). In Magway, 14% of the members of the drafting commission were representatives of armed resistance groups, compared with 9% in Mandalay.

Civic–stakeholder legitimacy comes from women’s organisations, labour groups, peasants, ethnic/minority groups, students’ unions, strike groups, youth networks, and CDM civil servants. Although this category represents very diverse organs, three major groups significantly influence this layer: ethnic minorities, CDM participants, and strike groups. These three groups have demonstrated a relatively higher level of dominance over the political process, beginning with the drafting phase and continuing to the current stage of executive formation. Local bodies representing each group have emerged alongside the drafting process. These include the Sagaing Region Strike Forces[3], formed by strike groups in the Sagaing Region; the Sagaing Federal Unit CDM Civil Servants Council[4] and the Chin Ethnic Groups[5] of the Magway Federal Unit.

Yinmarbin-Salingyi Strike of Sagaing Region Strike Forces [6]

This inclusion reflects the social character of the Spring Revolution and broadens political participation beyond armed actors and elected officials. However, their roles often lack a clear constituency and accountability mechanisms, leading to overlapping mandates and the potential duplication of functions.

These sources of legitimacy combine and create a power structure characterised by negotiation, decentralisation, and collective decision-making. Clearly, the term “consensus” is frequently described in the interim arrangements (in Sagaing, it is the constitution) of three units.

Varied Models of Executive Power

The three units share common goals and similar political origins, but they adopt different models of executive power to adapt to the need to balance local power and drive the resistance movement forward.

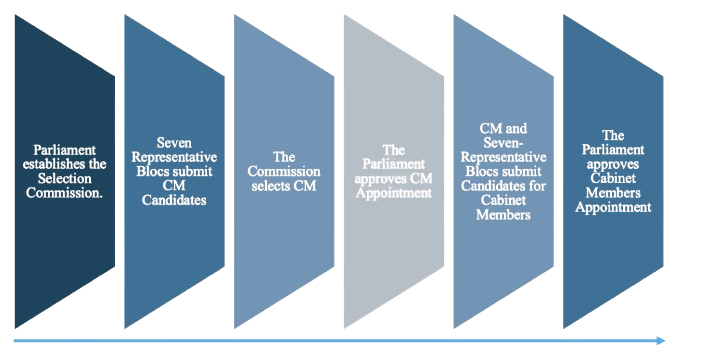

Sagaing adopts a highly collectivised executive structure. The five groups responsible for drafting the Sagaing Constitution have significant influence over executive authority, as Section 67 empowers them to scrutinise and select members of the executive. Their influence is further reinforced by Section 66, which permits only individuals belonging to the representative groups involved in the constitution-drafting commission to serve as cabinet members. The Chief Minister has very limited unilateral power, and the government operates through consensus among representative blocs. The Chief Minister does not have the executive authority to appoint or remove any cabinet members, including the Chief Administrator of the Naga Self-Administered Zone. Nor does the Chief Minister have the power to restructure the executive body under the constitution.

Process Diagram of Cabinet Formation in Sagaing

This model strictly prevents the concentration of power in any single actor but risks policy paralysis under collective leadership.

Magway presents the most codified and legally formalised model of executive formation among the federal units. Law No. 1/2023 of the Federal Unit Parliament institutionalises the drafting commission as a body composed of seven representative blocs, and these blocs subsequently become embedded as core political actors within the executive architecture. Their influence is structurally established through Sections 12(d), 61–63, and 152–154 of the Magway Interim Arrangement.

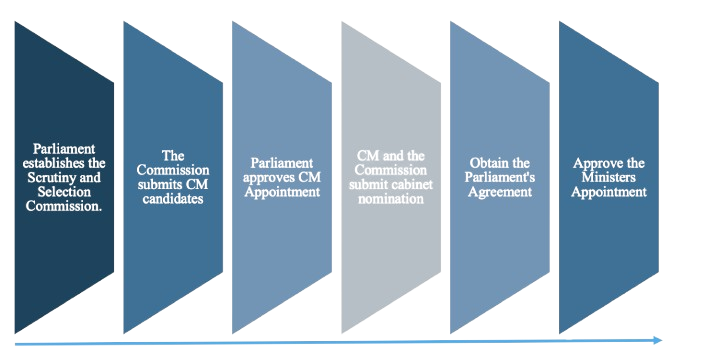

Process Diagram of Cabinet Formation in Magway

Section 12(d) predetermines the composition of the cabinet by limiting eligibility to members of these seven blocs, effectively transforming the drafting commission into a gatekeeping mechanism for executive authority. Sections 61–63 further empower the blocs to constitute the Selection Commission responsible for appointing cabinet members, including the Chief Minister. Each bloc nominates one candidate for Chief Minister, and the Selection Commission—comprised of representatives from these same blocs under Sections 153 and 154 determines the executive leadership. Although the Chief Minister is nominally authorised to nominate ministers, cabinet formation remains contingent on the collective consent of the seven blocs and subsequent parliamentary approval. In effect, the Magway model reflects the Sagaing protocol: the Chief Minister lacks unilateral authority to appoint, dismiss, or restructure the cabinet. Executive authority is instead dispersed across the seven blocs and the parliament. Consequently, Magway’s executive structure operates as a hybrid parliamentary model in which executive leadership is balanced, and at times constrained, by institutionalised checks from both parliamentary institutions and civil–political groups.

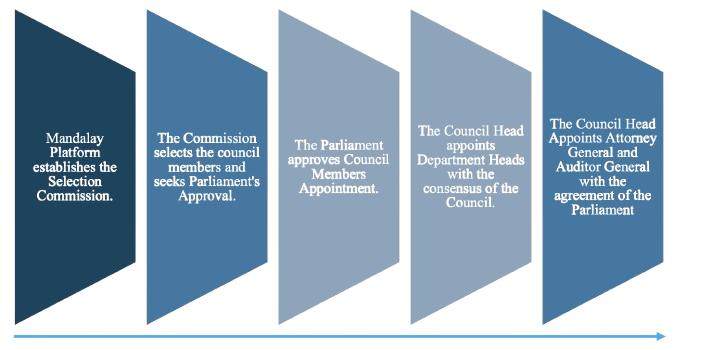

Mandalay adopts the least formalised and most centralised model, built around the Coordination Platform of revolutionary forces (the Mandalay Platform). Its Interim Governing Council is selected by the 11–15 representative blocs from the Mandalay Platform, followed by parliamentary approval. Unlike Sagaing and Magway, the Mandalay Executive Head is authorised to appoint, dismiss, or restructure the cabinet.

Process Diagram of Council Formation in Mandalay

However, there are no provisions in the arrangement guiding the accountability mechanisms of executive members. It remains unclear whether executive members will be held accountable to the parliament or to the Mandalay Platform. Mandalay has not yet published the members of the Mandalay Platform. The absence of detailed legal provisions on accountability reflects the politically sensitive security environment, where coordination takes precedence over legal precision.

Reference

[1] Section 119. The term of the Pyithu Hluttaw is five years from the day of its first session. Section 151. The term of the Amyotha Hluttaw is the same as the term of the Pyithu Hluttaw. The term of the Amyotha Hluttaw expires on the day of the expiry of the Pyithu Hluttaw. Section 168. The term of the Region or State Hluttaw is the same as the term of the Pyithu Hluttaw. The term of the Region or State Hluttaw expires on the day of the expiry of the Pyithu Hluttaw.

[2] CRPH, “Declaration on the Complete Abolition of the 2008 Constitution” [31 March 2021]. Available here: https://crphmyanmar.org/publications/statements/crph3103212/

[3] https://www.facebook.com/Sggstrike

[4] https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100091451325717

[5] https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=61580838481806

[6] https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=122196780116063633&set=pb.61551909016018.-2207520000&type=3

Read part (1) of the briefing paper here.

Share via: